AI expansion and the demand for new datacentres

After two decades of stagnation, US electricity demand is rising again. The primary driver of load growth is the rapid build-out of AI data centres, underpinned by record capital expenditure from the US hyperscalers.

At the same time, the reshoring of manufacturing and broader electrification are causing power demand to grow at its fastest rate since the 1990s. To meet this demand, the US must build generation capacity rapidly and at scale, and at the same time overcome emerging supply constraints such as long-interconnection queues, ageing grids, and increasing complexity as intermittent renewables displace baseload capacity.

In this insight, we examine the impact of the AI build-out on US power demand and comment on the likely constraints on growth.

Hyperscaler capex and US power demand

Power demand in the US is reaching an inflection. Over the previous two decades, energy consumption has remained broadly flat, with growth of around 0.4% per year, as energy-intensive industries have been offshored and efficiency gains have tempered growth. Over the same period, the energy intensity of GDP – the ratio of energy consumption to economic activity – has fallen by more than a third.

Why AI has triggered an inflection in this relationship

This dynamic is set to change, driven primarily by the build-out of AI data centres, but also by the reshoring of manufacturing and broad electrification of the economy:

AI data centres

AI data centres operate continuously and consume power at far higher densities than conventional facilities. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that AI queries can use 10-40 times more electricity per query than traditional search functions. Data centres are also getting larger and more complex as hyperscalers consolidate workloads to capture scale efficiencies.

Reshoring

According to Wood Mackenzie, investment in new US manufacturing facilities has risen 184% since 2020, led by sectors such as semiconductors, batteries, and advanced materials. The CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act have catalysed hundreds of billions of dollars in private investment, with over $500 billion in announced projects since 2021.

Broad electrification

Moving away from fossil fuels will require the electrification of transport, buildings and industry.

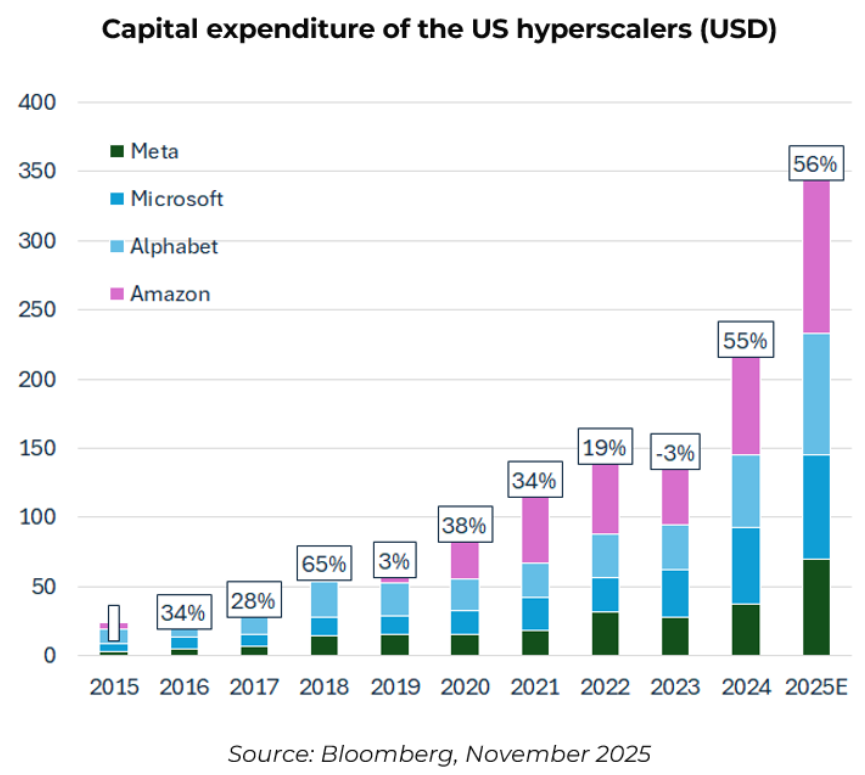

In the short term, Morgan Stanley expect AI data centres to contribute to around 60% of incremental power demand. In 2025 alone, the largest hyperscalers, Meta, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Amazon, are expected to make c.$350 billion in capital expenditure to build out their AI capabilities, and all have said that they plan to spend more next year.

Source: Bloomberg, Guinness Global Investors estimates; 30 November 2025

The impact of AI data centres on US power demand

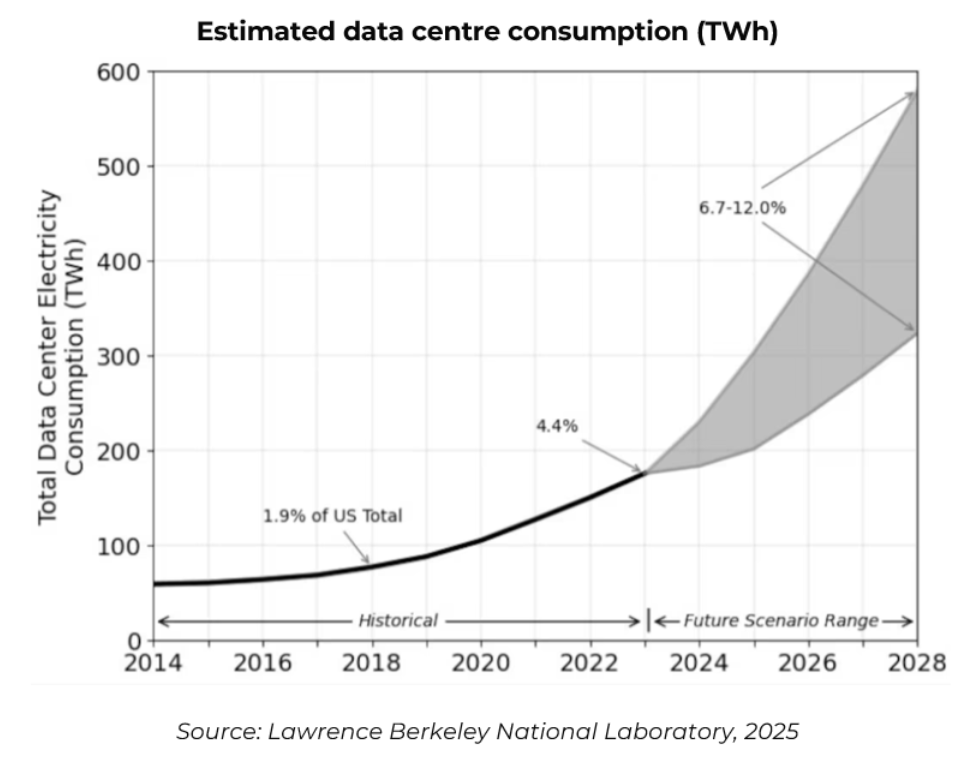

Estimates for the increase in power demand from AI data centres are particularly difficult to forecast and, as such, vary considerably. They are difficult to predict because both the efficiency of computing hardware and the scale of AI workloads are changing rapidly: each new generation of chips uses less energy per operation, but model sizes and usage are growing much faster, making future electricity needs highly uncertain.

Estimating existing data centre demand is similarly difficult, though the IEA puts its electricity consumption at around 180-200TWh in 2024, accounting for roughly 4% of total US demand.

Given this uncertainty, we see a range of forecasts:

- The IEA projects that data centre electricity consumption will grow by c.12-15% per year, increasing by approximately 240 TWh to reach c.420 TWh in total by 2030.

- The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) forecasts demand growing by 8-12% per year to reach between 325–580 TWh annually and account for 7–12% of total electricity demand by 2028.

- More bullish still, consultancies and sell-side analysts expect US data centre consumption to at least double by 2030, adding an additional 325–600 TWh of demand to the grid.

While forecasting exact demand figures is challenging, the direction of travel is clear. Assuming data centre demand grows by around 12% per annum, rising from c.180 TWh in 2024 to about 400 TWh by 2030, the US would need to add c.40 TWh of incremental generation capacity each year.

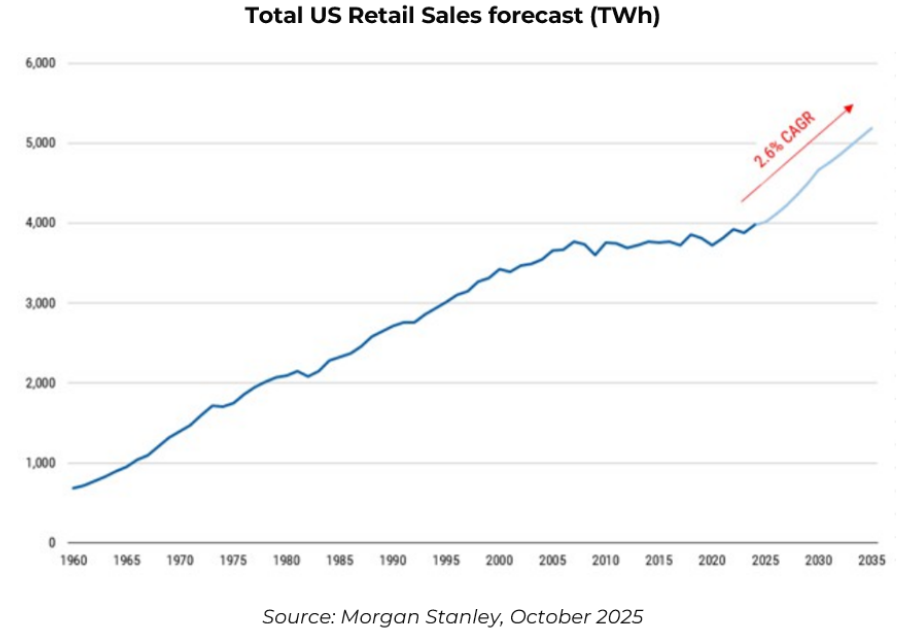

That equates to about a 1% annual increase in total electricity output before factoring in additional demand from reshoring and broader electrification. Morgan Stanley estimate that in combination, AI, reshoring and electrification are likely to add c.900TWh of incremental demand by 2035, taking total US consumption above 5,000TWh.

This would imply load growth of 2.6% per annum, requiring c.90TWh of incremental generation a year.

How can the US meet this demand?

Meeting this surge in demand will require new generation capacity after years of under-investment. The US grid currently supplies c.4,300 TWh of electricity each year, meaning that supply will have to grow at c.2% pa., to add 90TWh of incremental demand to 2030.

NextEra, a portfolio holding and an operator of both fossil-fuel and low-carbon assets, outlines a scenario of rapid renewable build-out, supported by long-term capacity additions from natural gas and eventually, nuclear.

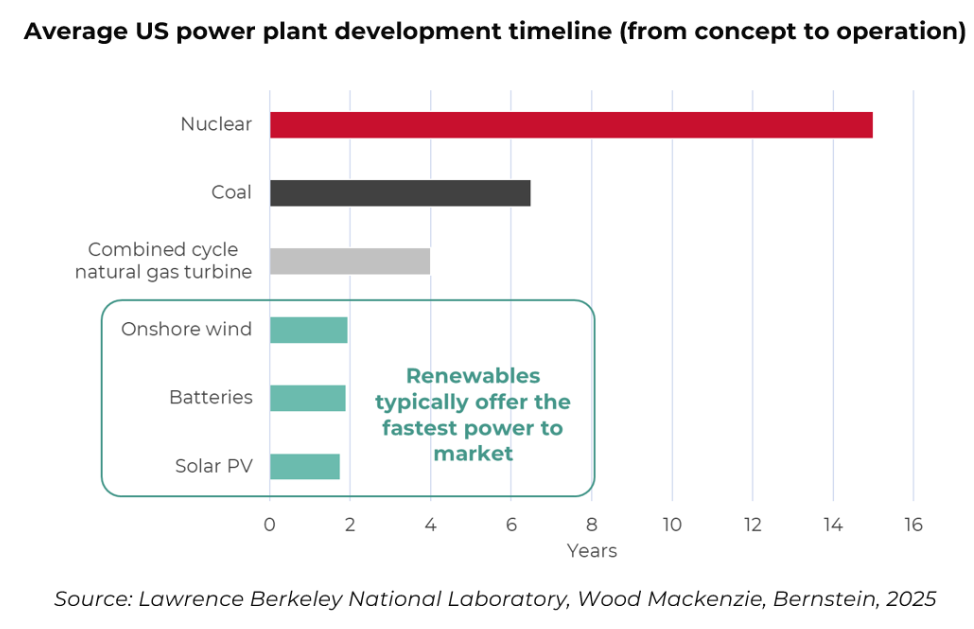

Underpinning this roadmap is the scale and speed of projected demand growth and the need for cost-efficient technologies that can be deployed rapidly at scale.

NextEra argues that the advantage of renewable technologies lies in their speed to market, flexibility, and cost advantages:

Renewables and storage

Existing and well-developed supply chains support rapid development, as does the availability of battery equipment. Storage projects can also be built on existing sites and connected to existing grids, and at the same time, battery costs have fallen sharply as the technology has matured and scaled.

Natural gas

Longer lead times, cost inflation, and underdeveloped supply chains mean that new or unplanned natural gas projects cannot meet all of the near-term demand, and in the long term, natural gas is a more expensive solution. However, given the rise of intermittent renewables, natural gas will play an important role in providing baseload generation.

Nuclear

After decades of underinvestment, supply chains need to be rebuilt, and technology developed before nuclear can contribute meaningfully to the generation mix. Plans to restart retired nuclear reactors are not expected to add generation until closer to 2030. If they come online as planned, they will be able to add c.15TWh of generation per year. However, timelines remain uncertain, with potential risks around regulatory approvals, financing, and construction delays.

Given these characteristics, NextEra see “firmed” generation (intermittent renewables backed by storage) as having the lowest levelized cost of generation in 2030. The company reports an estimated cost of $25-$50/MWh for new onshore wind (including storage) and $35-$75/MWh for new solar (including storage). This is considerably cheaper than new combined cycle natural gas at $85-$115/MWh and a small modular reactor (in 2035) at $130-$150/MWh.

This reality is playing out, as of the end of July 2025, 93% of new capacity has been renewables, with 83% being solar and storage. The economics and scalability mean that renewables, in combination with storage, are the cheapest and fastest way to meet incremental demand.

What are the main constraints on matching the power demand?

Although utility-scale renewables are the best placed to meet electricity demand, the US is finding it increasingly difficult bring new generation online. Supply has become constrained by an outdated interconnect process, permitting delays, and supply chain constraints.

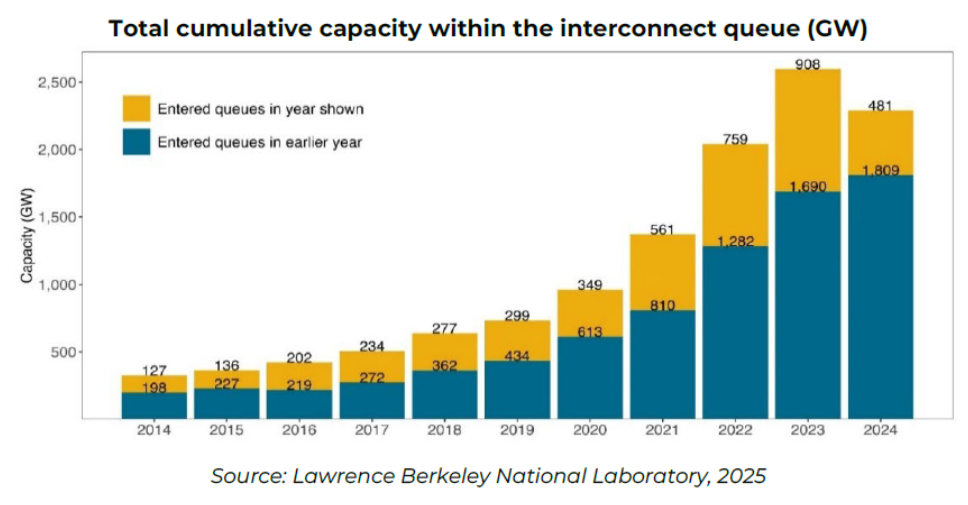

Official interconnection queues suggest that the US can meet incremental demand effectively, and quickly. As of 2024, some 2.2 TW of projects await connection. Around 42% of this pipeline is solar, 39% battery storage, 9% wind, and only 6% natural gas. If realised in full, it would represent a profound reshaping of the generation mix towards renewables and storage.

However, in reality, much of this interconnection won’t translate into real projects as some applications represent attempts by developers to increase their chances of getting connected by flooding the queue. At the same time, it doesn’t take into account actual grid constraints like the availability of power equipment and turbines.

In practice, however, the queue has become the central bottleneck. Developers report interconnection waits of four to ten years, with some markets, such as Northern Virginia, facing a minimum seven-year delay.

What is the largest constraint?

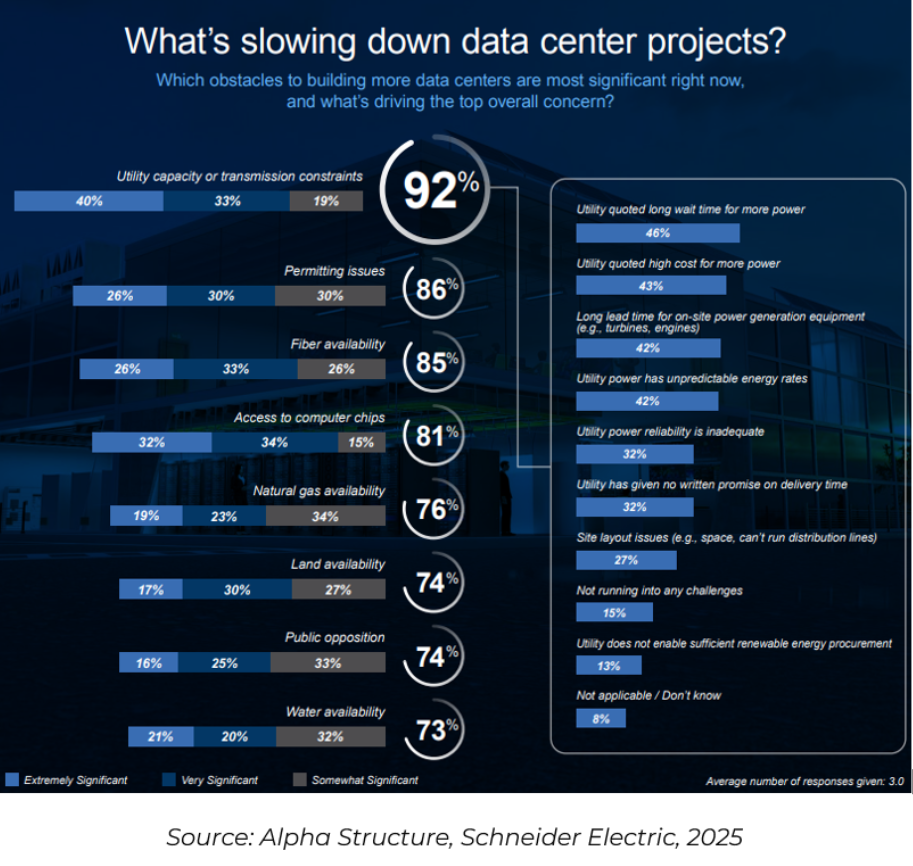

Given these factors, ‘time-to-power’ is likely the single largest constraint to the data centre build out in the US, as reflected in a recent survey conducted by Schneider Electric.

In the survey, respondents ranked utility interconnection delays and power availability well ahead of factors such as financing or equipment supply. Nearly half reported wait times of four years or longer to secure grid connections, and many cited a lack of available high-voltage capacity in prime data centre regions like Northern Virginia, Dallas and Silicon Valley.

What is the balance between sustaining existing infrastructure and building for the future?

To achieve these efficiency gains and integrate battery technologies, significant investment is needed to upgrade an already ageing grid. In its Net Zero scenario, BNEF estimates that approximately $500 billion of transmission and distribution investment will be required over the coming decade, with cumulative spending reaching around $1 trillion by 2035.

As roughly half of current grid capex is needed merely to sustain existing infrastructure, this indicates that an incremental $500 billion of investment will be necessary to maintain reliability while simultaneously expanding the grid to accommodate electrification and surging data-centre demand.

Long-term forecasts from William Blair and Morgan Stanley suggest a similar level of capex in order to integrate intermittent renewables into the existing system. Encouragingly, policy momentum is building: the DOE’s Grid Deployment Office has begun allocating over $20 billion in grants and loan guarantees, FERC has finalised new long-term transmission-planning rules, and utilities such as NextEra, Exelon, and PPL have already raised their grid-capex guidance in response

How should the US respond to the anticipated growth?

The build-out of US data centres is advancing rapidly and is backed by substantial, long-term investment from the country’s leading hyperscalers. In combination with the reshoring of manufacturing and broader electrification, the US will see its electricity demand grow at around 2.6% over the next decade.

To enable growth on this scale, the US must accelerate investment into transmission and distribution infrastructure, address persistent interconnection bottlenecks, and take a pragmatic view of which generation sources can meet near-term needs.

Read our other insight on AI themes: Are we in an AI bubble?

Risk: The Guinness Sustainable Energy Fund and WS Guinness Sustainable Energy Fund are equity funds. Investors should be willing and able to assume the risks of equity investing. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency movement; you may not get back the amount originally invested. The Funds are actively managed with the MSCI World Index used as a comparator benchmark only.

Disclaimer: This Insight may provide information about Fund portfolios, including recent activity and performance and may contains facts relating to equity markets and our own interpretation. Any investment decision should take account of the subjectivity of the comments contained in the report. This Insight is provided for information only and all the information contained in it is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete; any opinions stated are honestly held at the time of writing but are not guaranteed. The contents of this Insight should not therefore be relied upon. It should not be taken as a recommendation to make an investment in the Funds or to buy or sell individual securities, nor does it constitute an offer for sale.