Edmund Harris looks at China: Long term plans, short term pain

Director, Chief Investment Officer, Portfolio Manager

Marketing and Communications Executive

So how do you think investors should be thinking about China today?

Edmund Harriss

Well, as we know, the Chinese Government wields an outsized influence on the Chinese economy, and particularly on industrial policy. For many years, the deal has been that so long as they improve the standard of living for the population, then they can remain in power. And they have been very successful in that, the alleviation of poverty has now been astonishing. They have raised that economy from borderline starvation, for many, to a middle income economy, and it's now the second largest in the world.

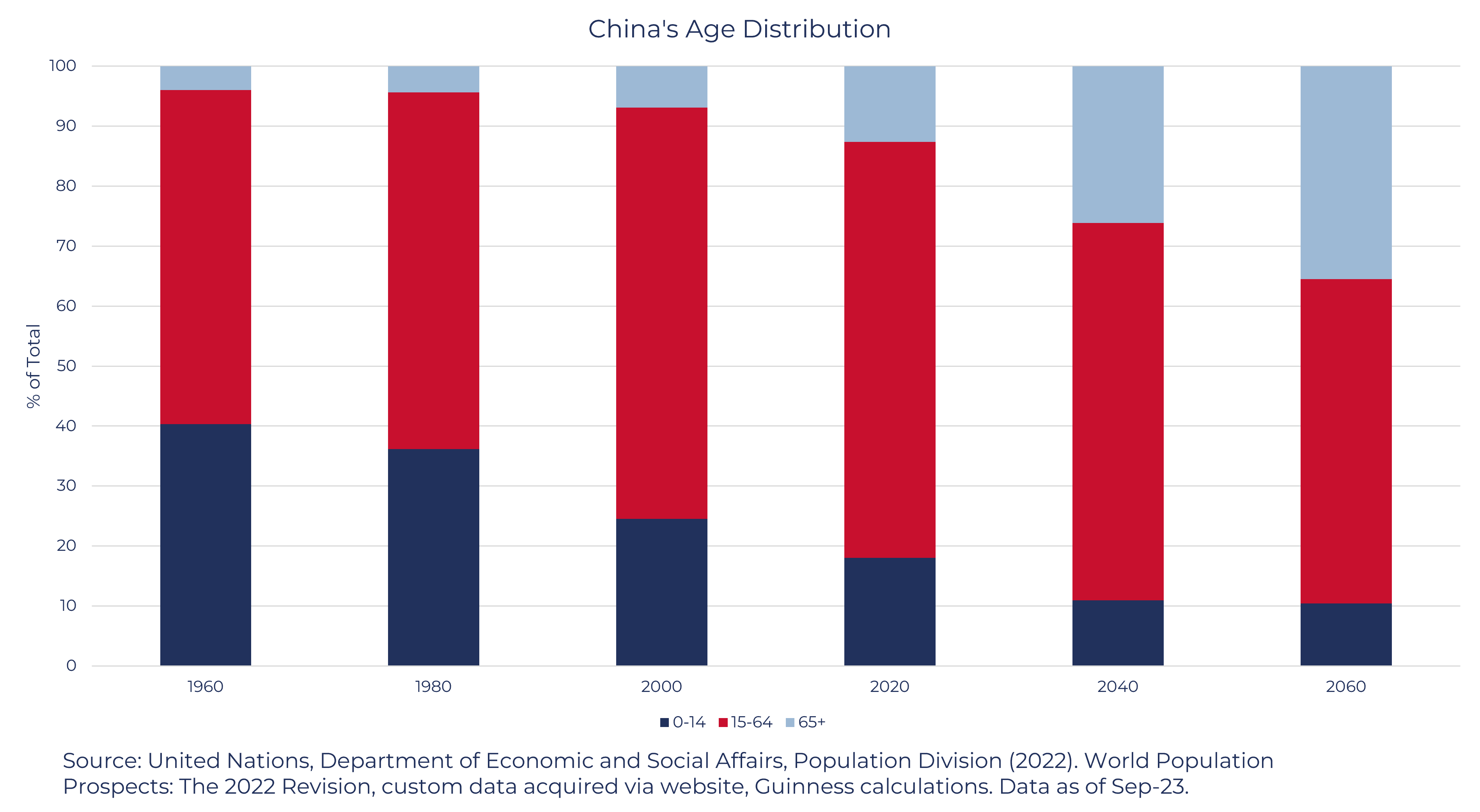

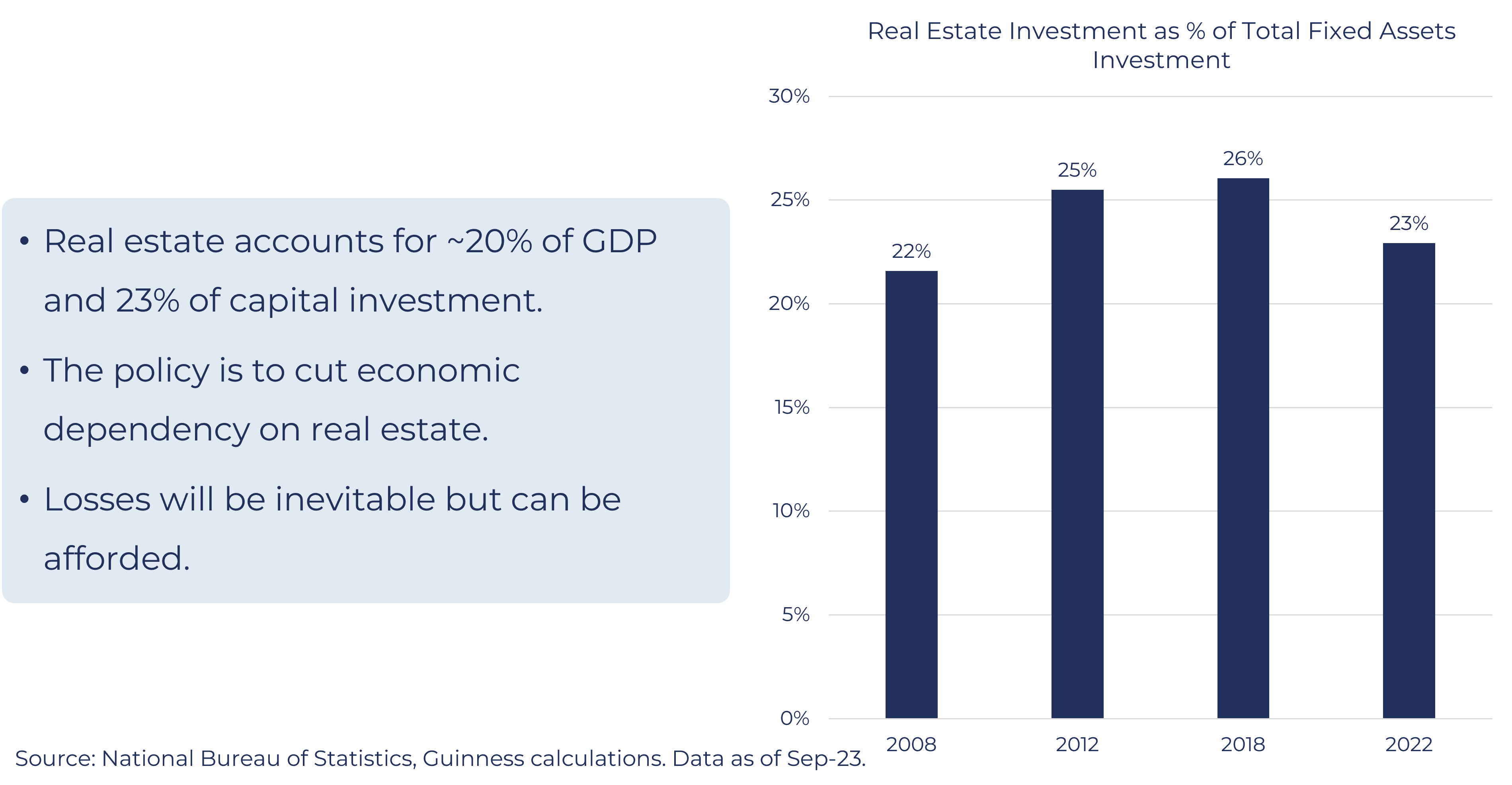

Today, though they are facing two particular headwinds, firstly, a demographic challenge, which is specifically the shrinking population and a shrinking labour force and ageing population that they now have to try and develop an industrial plan and growth policy to adjust for these conditions. And they also have to face the legacies of the past, a property sector which drove growth over the last 20 years, has outrun its usefulness. Excess property has been built, and there is a pile of debt based on that property sector.

So they need to complete that transition. But from our perspective, China's well capitalised, it's a lot richer than it used to be. There are the resources there to deal with the legacies of the past, and investors should now be focusing on those long term structural growth themes of where China is going tomorrow. And we divide our investment strategy for China into 7 long term structural growth themes, industrial policy is reflected through themes like sustainability, manufacturing upgrades or cloud computing, Artificial intelligence. Then there are the benefits to society accruing from that. Rise of the consumer, next generation consumer, healthcare, financial services.

So investors should I think see China as a going concern, an economy that is getting richer that has the resources to manage the transition. And I think it represents a good long term investment opportunity.

Jessica Walsh Waring

Interesting. And how extensive and serious do you think the risks are from the property sector?

Edmund Harriss

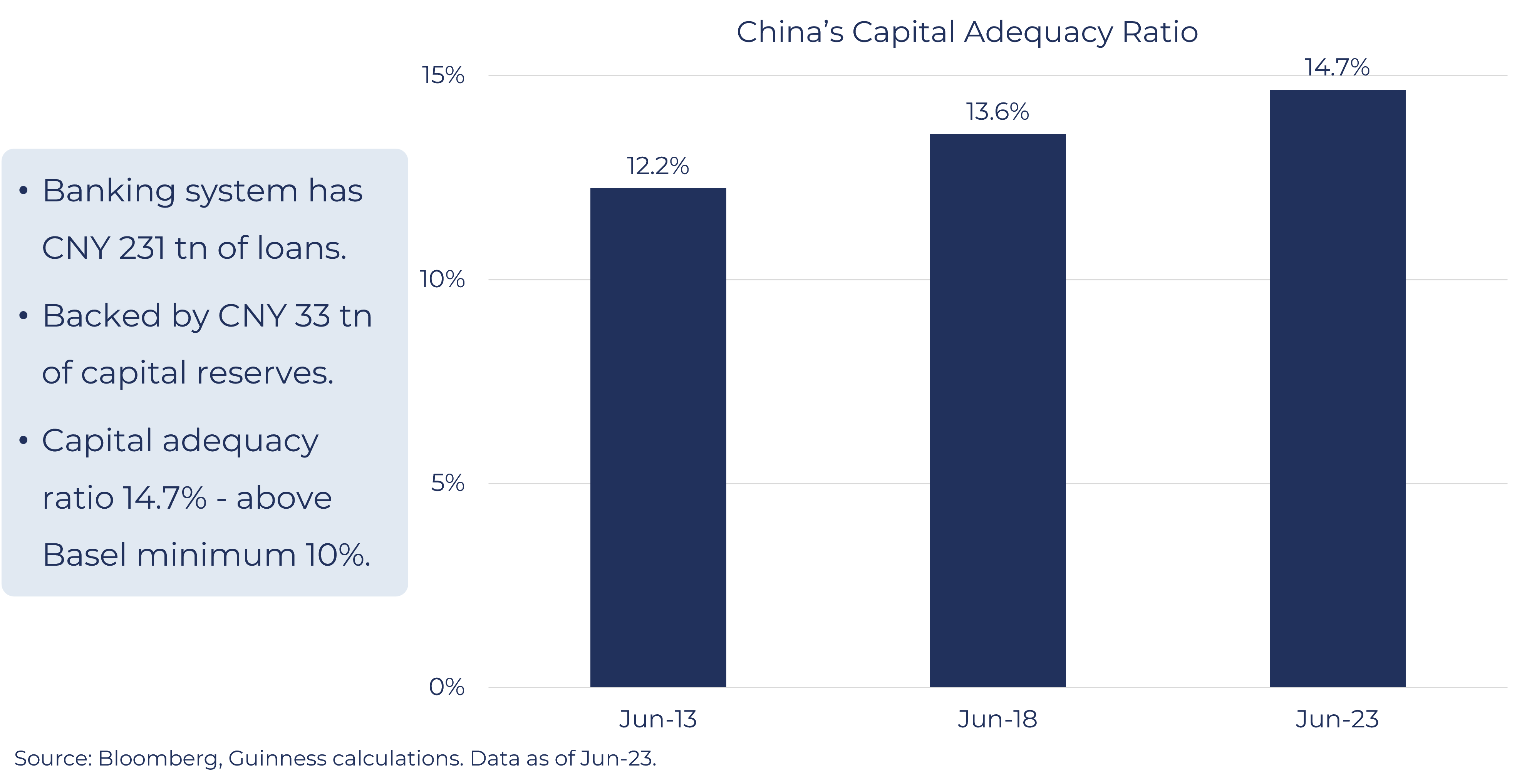

Well, it is true that the narrative has taken hold that the property sector itself represents an existential threat to China's financial system and therefore its ability to achieve its goals of making China into a high income economy. So what we need to do is to put some numbers around that. Is the financial system strong enough to cope with the unwinding of the property sector and the writing down of that debt or the repayment of that debt? And our assessment in short is yes, it is.

But if we put some numbers on it, China has around $33 trillion of loans outstanding in the system, and against that they have about four and a half trillion of capital. So that's about 15% or so. And the basic level that's required according to Basel Accord. Is that a financial system should have at least 10% of capital and reserves against the loans that they have outstanding and China's got half as much again. So there is a buffer.

So if we then look at loans extended to the property sector, that stands at around two and a half 2.6 trillion, about two trillion have loans have been made by the banks and the balance has been extended through bond issuance and through wealth management products. So we can do some simple stress testing. If we assume, say, that half of those property loans go bad that they're non performing loads and then you say well, out of that 1.3 trillion of non performing loans, 80% of those need to be written off. Think of all those flats that nobody's living in. They're no good to anybody. The only thing to do is to knock them over and forget about them. If we assume then that 80% need to be charged off. That's a $1 trillion cost against 4 and a half trillion of capital. Still leaves them with plenty in hand over 10% of capital is available. So the financial system still goes on.

If you look at it another way and say well, property has been such a big driver of the economy, you've got construction, you've got materials, you've got equipment, and you've got this sort of multiplier effect. So if you assume then that the property sector is going to shrink and this is going to have an economy wide impact. You could look at it in another way and say in the economy as a whole, the banks are reporting 2% non performing loans. Let's assume they're 10%. Let's assume that it's a much more widespread problem. And in that case you have about 3 trillion of loans then that are going bad. If you assume a 40% charge off against that, you're still left with around 10%-11% of capital reserves. So what we've done is essentially shake the tree and seeing if anything rattles anything falls off. Clearly, it's going to be painful for the financial system. But if the financial system can hold. And we're not going to see a crisis there. Then the conversation needs to move on. We could say there's enough capital in the system. It's going to be painful. There are going to be financial losses. Banks or smaller banks or smaller financial institutions will fail, but they can be supported by other parts of the system. China is still a going concern and therefore these newer industries that they are focusing on still have the capital resources to function, so therefore investors can then take their choice. Stay away from this. Move into that. There are opportunities still there.

Jessica Walsh Waring

So you say that it's going to be financially painful. How likely do you think it is that we're going to see financial crisis in China and what do you think that would look like for investors?

Edmund Harriss

I think the prospects for a financial crisis are low and the reason for that is that there is already enough capital in the system to absorb the losses that we can see, that are possible. You would have, even if we assume, that all these losses come together and happen now. In the space of the next six months, the system is strong enough to cope with it, and furthermore, the sources of capital are primarily domestic. So in contrast to other emerging markets, say somewhere like South Africa, which is heavily exposed to external financing, Chinese financing is domestic. And if you control the sources of capital and you control the institutions that are making the loans, you then have a much greater ability to spread the burden. So financial crisis I think is low.

But if one were to occur, then everybody should be interested in this. This is not a matter just of polite interest. China holds $3 trillion plus of foreign exchange reserves. They're held in the form of government bonds issued by the US and Europe primarily. If there was a financial crisis, those would have to be sold and the money repatriated so you would find then that global interest rates and global bond yields would be pushed higher.

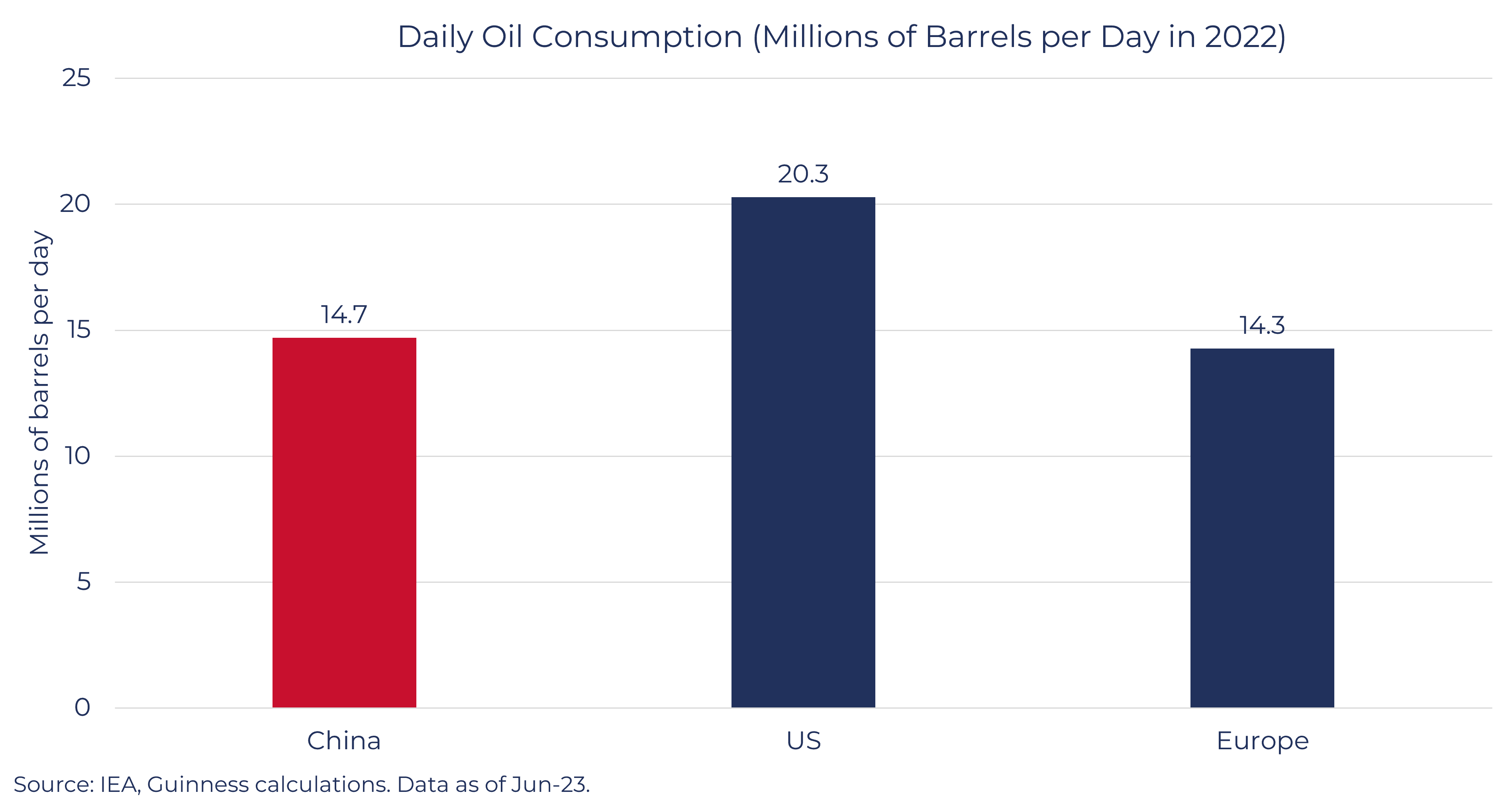

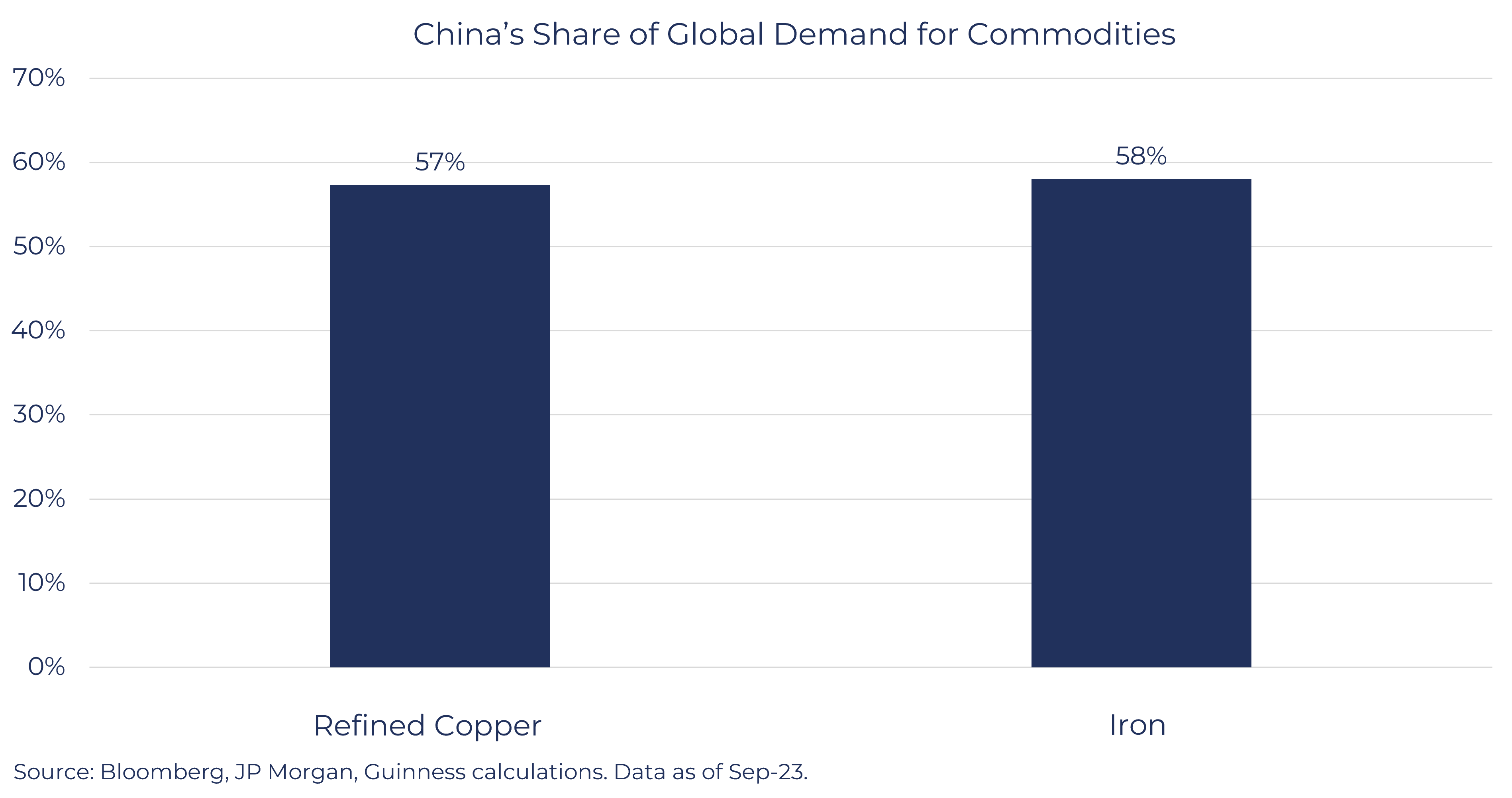

In the case of oil, China consumes about 15,000,000 barrels per day. The oil market is pretty sensitive to changes in demand of about one to two million barrels a day. So if China were in a financial crisis and that demand would half so 7,000,000 barrels demand would disappear. You would feel that ripped through the oil sector. They're the biggest customer for industrial metals, iron ore and copper. If demand were to slump there, then that would be felt through Brazil, Chile, Peru, South Africa, Angola and into Asia and particularly through India.

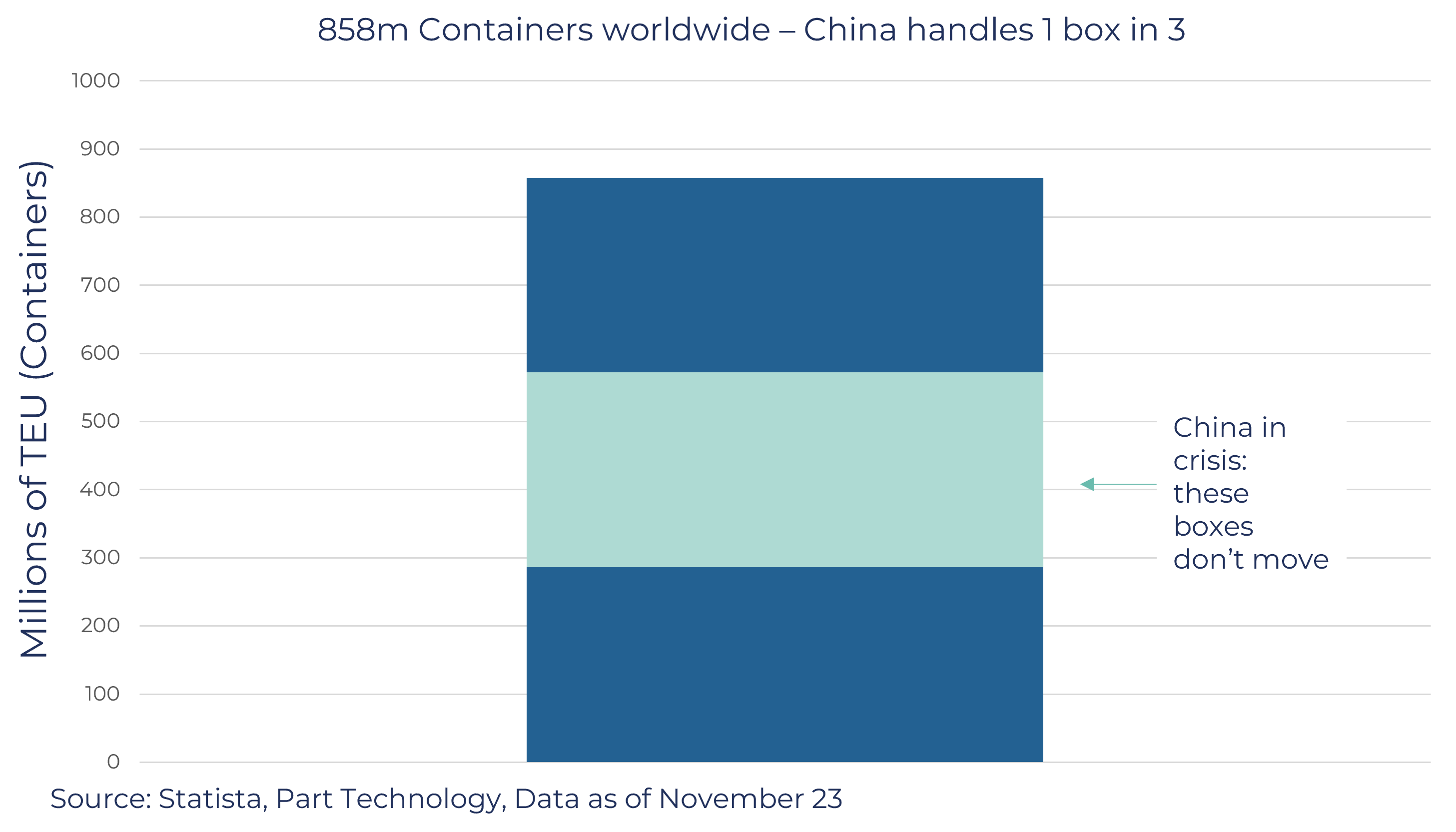

So that would be then ripping through the entire emerging markets complex. And then there's trade. China has built its success over becoming a manufacturing centre of increasingly high value items. To the extent now that the trade and merchandise goods which is transported around the world in around 850, 860 million containers, China handles 1 box in every three. So if you were to take one box in every three out that these things do not move. They sit on the harbour side because letters of credit cannot be issued, so boxes don't go on boats and the boats do not move. Then the disruption to supply chains would be significant.

So, when thinking about the likelihood of financial crisis or whether one is sort of coming just over the horizon, happily we can point to there being no sign of this or any stresses or strains, either in bond yields, in commodity prices, in the oil price, or in trade.

So the impact would be huge, but I think that conversation is one that we can put to bed. That is not, by any stretch, a central case. It's not even a bear case. It's a remote likelihood, given I think the way China's financial system is structured.

Learn More about the Guinness Greater China Fund

The Guinness Greater China Fund invests in quality, profitable companies which give exposure to the structural growth themes in China.

The process is designed to give this exposure while mitigating the risks involved with investing in China. The Fund also has a valuation discipline designed to avoid overpaying for future growth.

Latest Greater China Insight: How to view Chinese Markets?

Chinese markets have risen significantly over the past two decades. However, depending on the benchmark that an investor uses to measure returns, the performance of Chinese markets can look very different. The difference between offshore and onshore (A shares) needs to be considered.

Responsible Investment

We define responsible investment in line with the UN PRI definition: a strategy and practice to incorporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions and active ownership.

We incorporate ESG factors into all our equity strategies and embrace the stewardship responsibilities which we assume as investment managers.