Sustainable investing: the problem with plastic

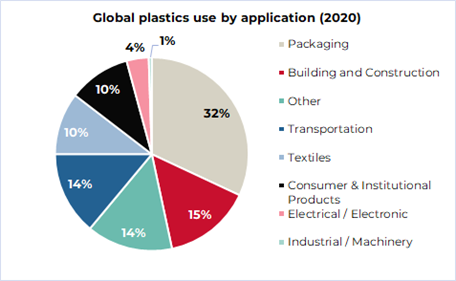

Since plastic as we know it today was invented in 1907, it has become embedded in modern life. Plastic - or, since the word refers to several different substances, plastics - refers to the highly adaptable synthetic polymers which can become different materials with a wide range of properties including flexibility, durability, heat and chemical resistance. This versatility, combined with the availability of low-cost fossil fuel feedstocks, has driven widespread adoption. Plastics are now widely used in consumer staples (in packaging), healthcare (disposable medical equipment), textiles (synthetic fibres) and transportation (lightweight vehicle components).

Plastic use is still accelerating

Plastics are now widely used in consumer staples (packaging), healthcare (disposable medical equipment), textiles (synthetic fibres) and transportation (lightweight vehicle components).

Source: Guinness, OECD, 2024

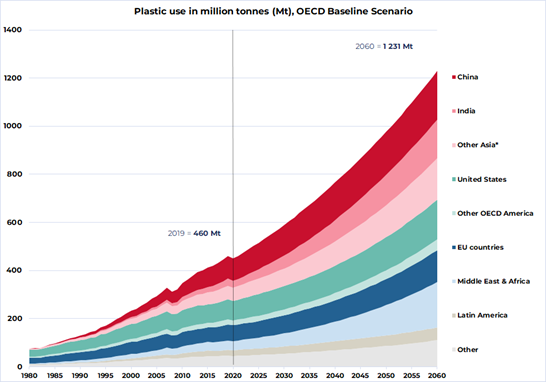

The OECD expects global plastics use to continue rising as population growth and improving living standards drive higher consumption. Demand is likely to be strongest in emerging Asian and African economies as they close the consumption gap with higher-income countries. In its 2022 Global Plastics Outlook, the OECD estimates plastic use will almost triple to 1,231 million tonnes (Mt) in 2060 (up from 460 Mt in 2019). Growth is expected to be driven primarily by packaging, construction and transport.

*excluding the Middle East

Source: Guinness, OECD, 2024

Why is it hard to replace plastic packaging?

In consumer staples, plastics play a particularly important role in food and beverage packaging. Plastic packaging helps protect product quality by providing an effective barrier to air and moisture, withstands a wide range of temperatures and acidities, and extends shelf life. Plastics are also lighter than glass or metal, which can reduce transport-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

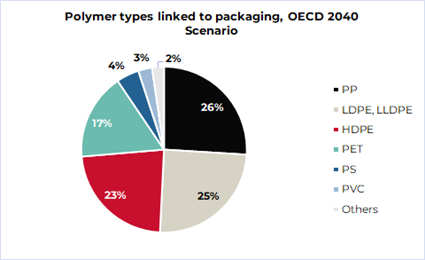

These functional benefits explain why plastics have become so widely used – and why replacing them is often complex. The four most common packaging polymers - polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP), high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and (linear) low-density polyethylene (LDPE or LLDPE) - are each designed for specific performance requirements, safety standards and regulatory constraints. For example, while PET can deliver lightweight strength to a Coca-Cola bottle, HDPE can provide high chemical resistance and toughness to a Procter & Gamble (P&G) laundry detergent bottle.

By 2040, the OECD expects plastics packaging use to increase by around 70%, from 139 Mt in 2020 to 234 Mt, demonstrating the scale of the sustainability challenge.

The sustainability challenge with plastic

Rising plastic production will increase pressure on waste collection and treatment systems. Globally, only around 10% of plastic is recycled. While recycling volumes are expected to rise, inadequate collection systems, weak sorting infrastructure and low economic incentives for recovery mean that large volumes of recyclable plastic are instead incinerated or disposed of into landfill. Over time, plastics fragment into microplastics, which can leak into land and aquatic ecosystems.

Plastic pollution also raises important social and human rights considerations. Regions with less mature waste infrastructure are expected to see the fastest growth in plastic use and leakage. The OECD expects annual plastics leakage across the Middle East and Africa to increase more than triple between 2019 and 2060, reaching 3.2 Mt, while leakage in the EU is expected to decline by around 35% over the same period.

In response, regulators are introducing measures such as bans on certain single-use plastics, recycled content requirements, and 'extended producer responsibility' schemes. For consumer staples companies, this evolving regulatory landscape presents both risk and opportunity. Exposure to fragmented and tightening regulation can increase costs and complexity, while also incentivising innovation and investment in circular solutions.

Our engagement with consumer staples companies

Given the materiality of plastics to both environmental outcomes and business models, during 2025 we engaged with several consumer staples holdings including Coca-Cola, Danone, Mondelez, P&G, Unilever, and Yili Group.

Through our engagement we sought to understand how companies are navigating these challenges in practice, where progress is stalling, and why the transition towards plastic circularity is proving complex.

Fragmented regulatory landscape

A consistent theme across our engagements was the fragmented and occasionally inconsistent nature of plastic regulation. Companies highlighted differences in post-consumer recycled (PCR) requirements and recyclability definitions between regions and product categories.

Danone noted that polystyrene (PS), used for its yoghurt pots, is considered recyclable in France but not in the UK or Canada. In its water business, Danone mainly uses PET packaging (used in around 70% of all beverage packaging). While recycled PET (rPET) is widely permitted in food and beverage packaging in the UK and Europe, where Danone is looking to transition its Evian and Volvic bottles to rPET, it is not yet approved for food and drink contact in China. Elsewhere, rPET is prohibited in US pharmaceutical packaging due to hygiene concerns.

Operating in multiple jurisdictions requires companies to navigate a patchwork of rules, which increases costs and slows the adoption of scalable solutions. Some are therefore advocating clearer and more harmonised global standards that maintain safety while enabling scale.

Infrastructure remains a significant constraint

Some companies highlighted to us that the recyclability of packaging often depends less on the material design and more on local collection and recycling infrastructure. While many plastics are technically recyclable, infrastructure has not kept pace with their usage in many regions. Better infrastructure could, in turn, support the availability of recycled plastic for companies to use in their production lines.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes can help address this challenge by placing greater responsibility on plastic producers and distributors. While companies tend to agree with the premise, we heard a recurring concern over ensuring that EPR fees are transparently reinvested into infrastructure rather than simply functioning as an additional tax.

Where infrastructure is underdeveloped, some companies are investing directly in collection systems. For example, Danone’s Aqua brand co-financed a PET collection project in Indonesia with Veolia, increasing the supply of PET feedstock at Veolia’s local recycling facilities. The model is now being replicated across the Indonesian archipelago, focusing on remote areas that face significant waste infrastructure challenges.

EPR schemes vary considerably. Seven American states are implementing packaging EPR laws, with a further twelve considering legislation. Each state has differing timelines and producer requirements.

Trade-offs between plastics, climate, and nature

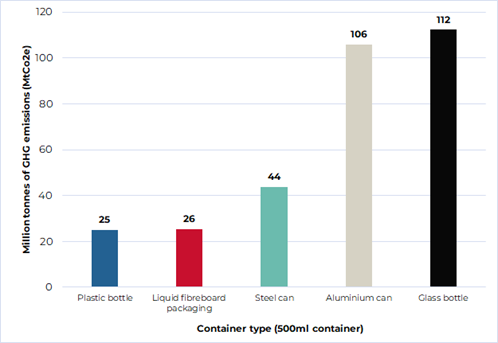

Materials such as bioplastics (plastics derived from biomass sources), aluminium, glass, cardboard and paper are often seen as substitutes for plastic packaging. Each, however, has its own environmental footprint to consider. If deployed at scale, it is possible that these alternatives result in greater greenhouse gas emissions, land and water use, or pressure on natural resources than plastics overall.

To navigate these trade-offs, the companies we engaged with stressed the importance of evaluating packaging decisions through lifecycle analysis (LCA), to avoid shifting environmental burdens from plastic pollution to climate or nature impacts. LCAs consider environmental impacts over a product’s full life cycle, from manufacturing and use to end-of-life, allowing companies to compare materials across multiple environmental metrics, applications and regions.

Plastic produces less emissions in the manufacturing stage when compared to alternatives

Plastics often perform favourably compared to alternatives at the manufacturing stage. A 2019 study by Imperial College London examined the production-phase emissions that would have been incurred if every 500ml PET bottle produced globally in 2016 had been made from alternative materials. As shown below, plastics performed well in these terms against common alternatives.

Source: Imperial College London (2019), “Examining material evidence: the carbon fingerpint”

The Imperial study then extended its analysis across 73 LCAs, covering a broad range of alternative materials. On average, the study found that replacing plastic packaging with alternatives would increase the weight of the packaging by 3.6 times, the energy use by 2.2 times, and the carbon dioxide emissions by 2.7%.

More recent research reinforces the complexity of these trade-offs. A 2024 review article in the Journal for a Sustainable Circular Economy, analysing papers published between 2019 and 2023, found that plastics can have a lower environmental impact than glass and bioplastics and some paper-based alternatives. While metals can perform well for beverage packaging, research suggests they tend to underperform in food packaging. In addition, a 2025 Michigan State University study highlighted metals’ higher impact on mineral resource use, something often overlooked in other assessments.

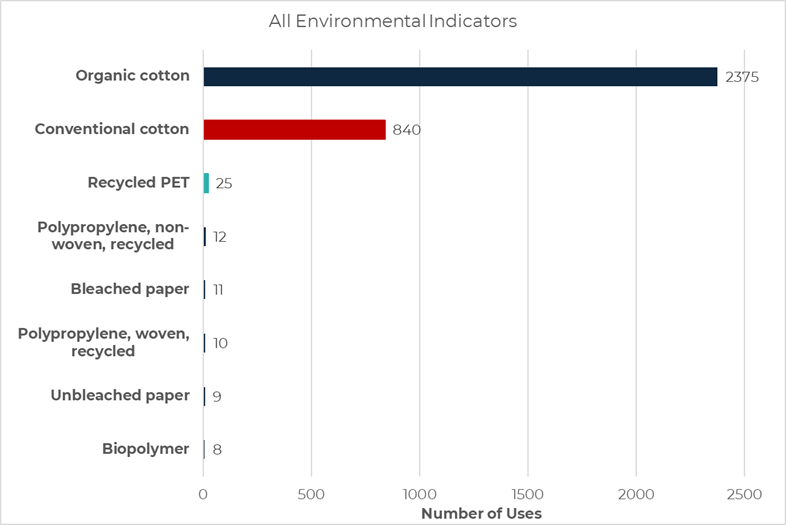

Findings are highly sensitive to underlying assumptions and methodologies. For example, when reviewing plastic bags, Dolci et al. (2024) found that plastic bags, whether reusable or disposable, can have a lower environmental impact than a cotton bag even when the latter is used 50 times. By contrast, an earlier report from the Danish Environmental Agency estimated an organic cotton bag would need to be reused more than 2,375 times to have the same environmental impact as a single-use plastic bag.

Source Danish Environmental Protection Agency (2018). “Environmental impact of different types of grocery bags. Number of times a given grocery bag type would have to be reused to have an environmental impact as low as a standard single-use plastic bag.”

Historical policies are impacting what's prioritised

Policy priorities also influence which environmental metrics receive the greatest attention. Following the 2015 Paris Agreement, reducing CO2 emissions became the primary focus of climate policy, often drawing attention away from factors such as land use change, biodiversity, water use, and deforestation. In recent years, these nature-related impacts have been re-emphasised in policy discussions, for example through the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. This evolution highlights the importance of harmonised policies that consider both climate and nature outcomes.

Moving away from plastics clearly introduces new trade-offs. Paper-based alternatives may increase water use and raise deforestation risks unless certified as deforestation-free. Procter & Gamble emphasised its use of LCAs to assess packaging choices against emissions, water, and land-use impacts, reinforcing the need for integrated decision-making rather than single-issue solutions. Danone also pointed to progress in reducing plastic content in bottles (by making bottles thinner) and, where LCAs indicate a lower environmental impact, shifting some sparkling water products to cans.

How are companies overcoming this?

Despite the challenges, companies are investing heavily in R&D, advanced recycling technologies, improved packaging design and collaborative industry initiatives.

Procter & Gamble described how long-term R&D investment can enable higher recycled content while maintaining product safety. For some of its liquid products, recycled plastic is “sandwiched” between layers of virgin plastic, ensuring regulatory compliance while allowing increased use of recycled content.

The R&D challenge varies between plastics. Unilever noted that flexible plastics such as sachets present a significantly greater challenge than rigid packaging due to their low cost and functional performance. While the company is testing alternatives such as small bottles, refill models, and return schemes, progress remains highly location-specific and no scalable solution is yet available, reinforcing the need for cross-industry collaboration and innovation.

What this means does this mean for our stewardship and investment approach at Guinness?

Our engagement programme shows that plastic exposure remains a material issue for consumer staples companies, but also that many of our portfolio holdings are actively working to reduce plastic use, improve recyclability and support circular outcomes.

A consistent message from companies was the call for clearer, more harmonised regulation and for EPR frameworks that genuinely support infrastructure development. From an investor perspective, we see a critical role for stewardship in encouraging transparency, outcome-focused reporting and continued investment in solutions that balance plastics reduction with climate and nature goals.

Looking ahead

Finding scalable alternatives to plastics will take time. Plastics remain widely used because they help companies meet strict product quality, safety and regulatory standards at low cost. However, the direction of travel is clear.

Through ongoing engagement, we will continue to monitor how companies translate ambition into measurable progress, particularly through R&D, infrastructure investment and collaboration. We believe that companies able to navigate these complexities thoughtfully, recognising trade-offs, investing in innovation and engaging constructively with policymakers, will be better positioned for a future shaped by circularity, regulation and rising stakeholder expectations.

This Insight may provide information about Fund portfolios, including recent activity and performance and may contain facts relating to equity markets and our own interpretation. Any investment decision should take account of the subjectivity of the comments contained in the report. This Insight is provided for information only and all the information contained in it is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete; any opinions stated are honestly held at the time of writing but are not guaranteed. The contents of this Insight should not therefore be relied upon. It should not be taken as a recommendation to make an investment in the Funds or to buy or sell individual securities, nor does it constitute an offer for sale.